Contribution Margins with BowTiedOpossum

Level 2 - Value Investor

Welcome Avatar! Today we’re bringing in a E-com vet to go over Contribution margins. To give a feel for the content and after that we’ll have him come back shortly with a post on Uncommon Marketing/Sales Strategies. Anyone in the know, understands sales/marketing is everything and your logo/color scheme is largely meaningless. With that handing it over to Opossum!

Today we’re going to cover one of the most important topics to scaling your ecom business. Outside of attribution of course… Contribution margin is often misunderstood & foreign to people that are used to managing a business based off of a normal P&L.

What is contribution margin?

Contribution margin, or unit margin, or flow through profit, is the profit on a sale after the variable costs.

Think of your expenses in two parts.

Variable Costs: Manufacturing product, shipping, Shopify transactional fees, boxes, pick & pack fees, Amazon referral fee, apps that charge a % of revenue or a fixed cost per transaction, etc.

Variable costs stay a fixed percent of the percent of revenue, no matter how much you sell. Your 2.9% or 2.6% or 2.4% credit card fee on Shopify is the exact same on every *incremental unit*. So if it’s the same on every incremental unit, it’s going to be the same percent of total revenue no matter how much you sell.

Different channels will obviously have different variable costs. This is very channel specific. You won’t be paying an Amazon referral fee on DTC orders and you won’t be paying Shopify transactional fees on Amazon orders.

Fixed Costs: Salary, services, fixed software costs like Shopify/email/SEMRush/etc., debt, etc.

Fixed costs change as a percent of revenue when you sell less or more. If you’re selling 1 unit a day, your Shopify subscription may be 5% of monthly revenue. When you’re selling 100 units, it will be 0.05%.

Two things to note here. First, fixed costs are rarely fixed. If you go from selling 5 units per day to 5k units per day, you’re obviously going to have to hire more staff, upgrade your Shopify plan, bring on more software, etc. Second, variable costs actually do come down as you scale. You get discounts on larger orders, economies of scale, etc.

The point of this is to look at the next incremental unit. NOT the next incremental 5k units you sell.

How are you going to manage your business around contribution margin?

Marketing. You need to figure out what your contribution margin is so that you can figure out how much you can spend to acquire a customer profitably. One customer profitably. Not whether your entire business is profitable.

All you need to do is to make at least $0.01 off of each customer after marketing and as you grow, your fixed costs will be covered. After your fixed costs are covered, that’s where the excess money falls to the profit line.

Variable Costs + Fixed Costs + Advertising + Profit = Revenue

On a unit basis this becomes: Revenue - Variable Costs = Contribution Margin

Which means that: Fixed Costs + Advertising + Profit = Contribution Margin

Since we’re going to make the assumption that we’re only going to buy media on the unit level that’s profitable, the fixed costs will eventually be covered as we scale. Taken towards infinity, this then leads us to the assumption that everything other than variable costs can be spent on advertising.

Let’s take an example looking at it through two lenses. The numbers aren’t accurate because I had to make them round for simplicity sake. (You’re never paying $1 for shipping)

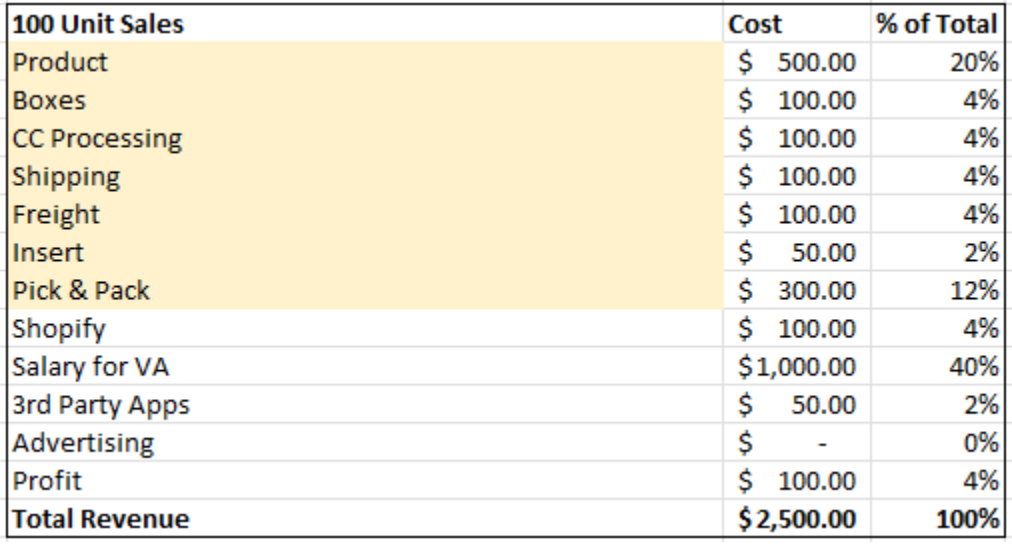

The below assumes you’re selling a widget for $25 and you sell 100 widgets this month. This also assumes your sales are coming organically and you’re not advertising

The variable costs are in yellow where the fixed costs, advertising, and profit are in white.

Most people that see this would say “I have can't advertise because I need to make payroll! I only have $100 in profit!” Wrong and misguided.

If your advertising is profitable on a contribution margin level, whatever is left over after the advertising will flow to the profit line.

Here it is on a unit level.

Since fixed costs don’t increase when you sell 1 more unit, they don’t matter as you scale. Once you get to a certain sales level, fixed costs are covered and any revenue minus the variable costs falls to the advertising and profit lines.

This means that if you spend anything less than $12.50 on advertising to acquire your next customer, the difference will be pure profit.

So if in this example, the owner of this business took the $1000 that was sitting in his bank to pay his VA at the end of the month and placed it into advertising… At a $10 Customer Acquisition Cost - CAC (remember, it has to be less than $12.50 to be profitable), his sales would double and it would look something like this.

Notice how the advertising pays for itself and the $2.50 ($12.50-$10) falls to the profit line.

$2.50 X 100 incremental units + $100 in original profit = $350 in profit.

So lets wrap up why this is so important.

Contribution margin tells you how much you can spend on acquiring a customer while still growing profitably. From a DTC perspective, you can also do this exercise using lifetime value if you want to push the envelope of growth if you have plenty of runway with cash to wait 3-12 months to be profitable.

Media Spend On and Off Amazon

If you want to translate this into what *incremental ROAS* you need, it’s a simple formula. Remember. Incremental ROAS and attachment ROAS are two completely different things.

Unit Revenue / Contribution Margin = Incremental ROAS needed to be profitable on a unit level. If you’re profitable on a unit level, you continue to scale until you’re not. Keep spending ad dollars until the ROAS comes down.

In the above example, contribution margin was $12.50 on a revenue of $25. A ROAS above 2 gives you a license to print money (thanks for the phrase BowTiedBrain).

If your contribution margin was $6.25 on a $25 AOV, it would take you a >4 ROAS to be profitable.

This is a cautionary tale as to why you need to control variable costs…

Affiliate Partnerships

With a variable cost at $12.50 and a contribution margin of $12.50, this gives you the leeway to to have your affiliate percentage close to 50% to acquire new customers. I highly advise you not to do this for a bunch of reasons, but you could…

This tactic is used with SaaS providers a lot where they use an extremely high affiliate commission on the first purchase to entice affiliates. They know that their customer base is going to be very sticky (repeat buyers increase LTV) so they can have a high affiliate commission and make up the profit difference on the back end of the customer lifecycle.

Wholesale

Variable costs are the “at cost” level of your product. What your company actually spends to get a product out the door. Contribution margin is the money you have to play with after the fact.

Continuing on with the above example, how should you price your products for a wholesale deal?

Your variable costs are going to be different with your wholesale channel than they were in the above DTC model, but let’s assume they’re the same.

If you strike a deal with Target and they want a first run of 10k units, how much profit will you make?

Retailers generally want a profit margin of 33%+. Using that as a gage, they’re going to buy your product for $16.75. Your variable costs are $12.50/unit, so you make $4.25/unit X 10k units or $42,500.

Normally it’s a slam dunk to get into retail from a brand exposure POV. Your contribution margin is $4.25/unit and you have no advertising costs to offset it so it flows straight to the profit line. Assuming Target doesn’t cannibalize your DTC sales…

Now what if the supply chain is locked up because of whatever reason and you can’t get product? You have the chance of running out of product given that there’s 100 cargo ships sitting off the coast of California that can’t dock.

You’re now sacrificing your normal $12.50 contribution margin for the wholesale $4.25 contribution margin. $8.25/unit X 10k units. Can your company sacrifice the $82,500 in contribution margin at your chance to get into Target?

This is a real example of what happened to a lot of DTC companies in the past few years

Hook & Build

The Hook & Build is a popular marketing strategy where you sell something cheaply to draw a customer in and try to get them to build their basket. A similar strategy is used in a lot of different scenarios.

You’ve probably heard of the “give away a free PDF in exchange for the customers’ email” strategy. It works on a cost basis because the variable costs for an incremental PDF is $0.

McDonalds uses this strategy with their $1 fountain drink. They price the item close to variable costs with contribution margin approaching $0 knowing that most all people will buy more than a coke.

The entire razor industry is built on the same idea. Sell the handle (acquire the customer) at unit variable cost and the profit comes later.

It all goes back to the same concept. Figure out your variable costs so that you know how much contribution margin you have to play with for discounts, commissions, advertising, wholesale, etc. All in the name of growth. With growth comes profitability.

Wrapping Up

That’s all for me today. I’d like to thank BowTiedBull for the chance to write a post. If you liked the material, follow me on X (BowTiedOpossum) and read through my posts on WiFi Money to learn more.

Disclaimer: None of this is to be deemed legal or financial advice of any kind. These are *opinions* written by an anonymous group of Ex-Wall Street Tech Bankers and software engineers who moved into affiliate marketing and e-commerce. We’re an advisor for Synapse Protocol 2022-2024E.

Old Books: Are available by clicking here for paid subs. Don’t support scammers selling our old stuff

Crypto: The DeFi Team built a full course on crypto that will get you up to speed (Click Here)

Security: Our official views on how to store Crypto correctly (Click Here)

Social Media: Check out our Instagram in case we get banned for lifestyle type stuff. Twitter will be for money.

More valuable content than what you learn at an MBA program. 👍

when this formula really 'clicks' in your mind and you implement it... life truly changes quickly. You broke this down so simply. Great work.